The Edo period was an incredible time in Japan's history. It was a time of peace and prosperity after the constant wars of the Warring States period. A time of social realignment, with the samurai class falling and the merchants gaining power. But most importantly, it was a time of national isolation.

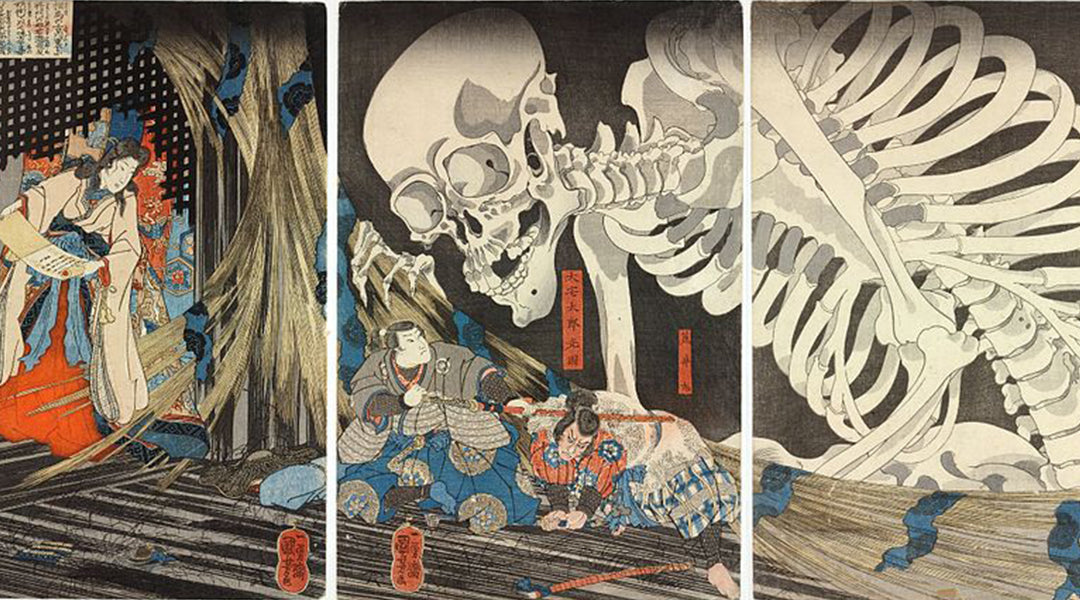

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre

Takiyasha the Witch and the Skeleton Spectre

Shortly after the Edo period began, the Shogunate started issuing edicts barring foreigners from entering or even trading with Japan. The government was suspicious of western ideas, particularly Catholicism, which the Spanish and Portuguese used as a tactic to colonize countries. The Shogun correctly saw this as a threat to his power and, except for Dutch traders, Japan's borders were closed to the Western world.

Locked country

The sakoku (lit: locked country) policy stopped Westerners from entering Japan or Japanese citizens from leaving, and it was in place for over 214 years. Sakoku coincided with the Edo rule and was one of the most peaceful and prosperous periods in Japanese history.

With Japan at peace and safe from invading ideas, and influence, Japanese ideas were free to flourish, buoyed by the newly wealthy merchant classes hungry for entertainment. To cater to this new need, the Shogun legalized new pleasure districts, the Yoshiwara, which became centers for Japanese culture.

These pleasure districts and their inhabitants became known as the floating world (ukiyo), and ukiyo-e (lit: images of the floating world) are our window into the floating world and the ideas it embodied.

This is the second article in a series on ukiyo-e focusing on the woodcuts themselves. In the first article: Ukiyo-e Part 1 – images of a floating world, we covered the background of the pleasure districts. And the final article in this series will discuss ukiyo-e's influence, both on Japanese tattooing and artists in the West. But in this article, we're looking at the ukiyo-e themselves.

The history of woodcuts

Throughout Japan's history, woodblock printing was used. Western-style moveable-type printing presses were introduced in the 16th century but did not catch on due to their association with Christianity. And they were outlawed when Christianity was banned in the early 17th century. From that point onwards, woodcut printing became the only form of printing in Japan.

One of the earliest surviving examples we have of printing is this scroll covered in Buddhist prayers.

Source: Princeton University

In 764 AD Empress Koken commissioned this scroll. The Empress had been removed from power by her cousin. While regaining her throne her cousin was killed. To show repentance, she commissioned one million of these scrolls along with wooden pagodas and had them placed in temples throughout Japan.

The printing process

It was in the Edo period when woodblock printing took off. The increasing literacy rates and growing prosperity of ordinary citizens meant more demand for written material. Printing was originally used to mass-produce hand scrolls as books, but it also gave rise to prints: ukiyo-e.

Initially, prints only had one color, but around the middle of the 18th-century multicolored woodblock printing, nishiki-e was developed. This video shows the process of creating multicolor prints.

The process is incredibly detailed and intricate and gives a unique handmade finish that changes organically. Prints created when the woodblock is fresh have clearer lines, while later prints show signs of wear on the printing block, and colors vary widely between editions.

Publishers

Ukiyo-e prints were commissioned by publishers and produced in a factory-style production process. The teams consisted of a designer, carver, and printer. An early form of copyright attached to the physical woodcut was in effect. Publishers would trade woodcuts, thereby trading the right to print the image on the woodcut.

Initially, printing was reserved for more expensive products like books and decorative prints. As the price of printing came down, prints became a more everyday item—everything from education and warning signs to advertisements referred to as hikifuda were printed using woodcuts.

Source: Osaka Prints: Example of a hikifuda

Ukiyo-e

One of the defining cultural achievements of the Edo period is the advancement of Japanese art and ukiyo-e in particular. Demand was strong in both the ruling classes and ordinary citizens for images of the floating world.

Ukiyo-e depicting the celebrities of the Edo peroid –Kabuki actors, sumo wrestlers, and courtesans– were very popular. Erotica, which was called shunga, were very popular, with most ukiyo-e artists producing erotica at some point throughout their careers.

Ukiyo-e were also used to depict the heroes of the day, including samurai, the tattooed firefighters of Edo and Sumo wrestlers. A particularly fierce battle between a group of sumo wrestlers and firefighters was immortalized in kabuki theatre and ukiyo-e's like the one below.

Source: Artelino

Later, when traveling became more popular, prints of landscapes were created to serve as souvenirs. These ukiyo-e acted as mementos of trips around Japan much like a modern-day postcard.

The Great Wave Off Kanagawa is one of the most recognizable ukiyo-e landscapes. It was created by Hokusai, one of Japan's most famous ukiyo-e artists, as part of his Thirty-six Views of Mount Fuji series. While not intended as a souvenir, it is one of its greatest ukiyo-e landscapes created by one of its most celebrated artists at the height of his creative powers.

In the following article, we'll be looking at how ukiyo-e influenced Japanese tattooing and its influence on Western artists once Japan opened its borders.

For more on ukiyo-e, check out the first article in this series and see our books and prints, like The UKIYO-E 2020.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.