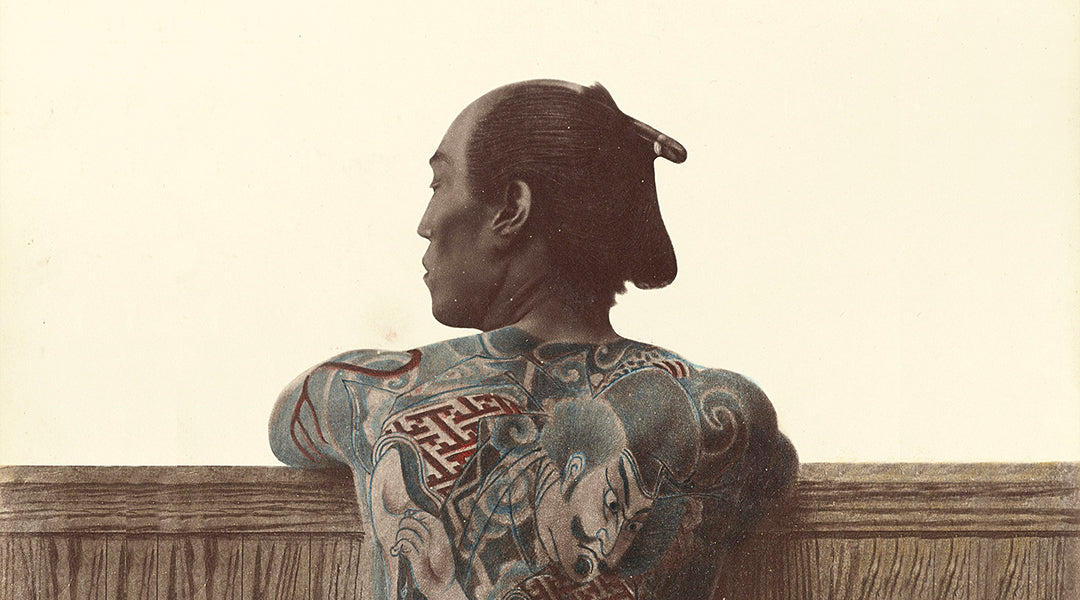

Japanese tattoos are famous throughout the world. They are much sought after by collectors and are lauded for their scale and delicate intricacy. The art form, called irezumi (literally: inserting ink), attracts tattoo aficionados from all over the world, many of whom spend years and millions of yen to acquire their horimono (bodysuit).

But closer to home, Japan has had an on-again-off-again relationship with one of their most famous artistic exports. So we wanted to take a trip back in time to explore how we got to where we are today.

A long time ago…

…and (depending on where you live) far, far away, there was tattooing on the island of Japan.

Source: Wikimedia

Source: Wikimedia

While it’s impossible to date exactly when tattooing started in Japan, there are indications of tattooing from as early as 5000 BCE. Some of the earliest representations of tattooing are from Japan –ancient clay figures with tattoos on their faces and bodies.

It’s unclear exactly when tattooing began to take on a negative connotation in Japan. Some sources peg it to the Kofun period. But it’s clear that it had acquired an unfortunate stigma from the 8th century when the shogunate started to use tattoos as punishment.

Permanent marker

Tattoos have long been used across civilizations as a punishment. The Greeks and Romans used them as a way to mark criminals and brand disobedient slaves, a practice they learned from the Persians. One of the most awful examples was the Nazi regime's use of tattoos to mark Jews permanently. And there is also a long history of criminals using tattoos to identify their own crimes or brand other criminals.

See Russian Criminal Tattoos and Playing Cards for examples of tattooing in prison.

Back to Japan and their criminal tattoos. From the 8th century, tattooing started to be used as a permanent marker of criminality. Serious crimes like murder or attempted murder would receive a face tattoo, with lesser offenses, such as theft, receiving arm tattoos.

Source: Pen Online

While head tattoos for a serious crime and arm tattoos for lesser offenses were probably common across Japan, the symbols weren’t consistent between the different regions. So, in theory, a person with a tattoo could move between regions and obscure the specifics of their crimes.

It was also possible to cover a punishment tattoo with a decorative one. A practice that was common in the Edo period owing to tattooing’s burgeoning popularity. Criminals were able to use tattoos to cover their criminal records.

See our article Tattoos used to be dangerous to learn the places where tattoos can still get you in trouble.

Edo period

The Edo period was a very exciting time for Japan in general–the economy was booming, and they could now afford a middle class. With tattooing, in particular, receiving a massive boost in popularity.

The Chinese novel Suikoden (The Water Margin) can take a lot of credit for the rise of the newfound interest in all things tattoo.

Check out Of Brigands and Bravery, which is the first English language reproduction of the original woodcuts commissioned for the first publication of Suikoden.

These woodcuts, and woodcuts in general, lead to a rise in the popularity of tattoos. Woodcut artists even started tattooing, using the same tools they used to create the woodcuts. A practice that gave rise to the term tebori (to carve) to describe tattooing.

The imagery of these tattoos and what they represented appealed to a broad range of people. It’s been speculated that merchants, barred from flaunting their wealth, got elaborate horimono as a secret status symbol. We know for sure that tattooing was worn by the yakuza and to members of ukiyo (the floating class) as an anti-shogunate statement.

See our article on The tattooed firefighters of Edo to learn about the Edo era firefighters. A group who were equal part heroes and brigands.

Open up borders, close up shop

Tattooing had been blooming all through the Edo era, and while not necessarily an accepted part of society, it was definitely a part. But at the beginning of the Meiji period, all that changed.

New emperor, new rules.

Emperor Meiji arrived, and he wanted to put his stamp on Japan’s history. He turned Japan from an isolated feudal state to an industrialized world power. And one of the first things to go was tattooing.

The ban on tattooing coincided with Japan opening its borders. It was thought that tattooing would give the world a bad impression of Japan, so tattoos had to go… or mostly go. The law forbade tattoo artists from tattooing Japanese citizens but didn’t say anything about foreigners.

Enterprising tattoo artists set up shops in Japan’s newly opened ports and tattooed any sailor who crossed their threshold. This led to Japanese tattoos being seen at ports throughout the world as sailors went from port to port.

These tattoos weren’t limited to junior sailor Lord Admiral Charles Beresford got a tattoo when he visited Japan, as did Prince Albert. There’s even a book called Japanese Tattoo and the British Royal Family about the royals’ love of Japanese tattoos.

But Emperor Meiji’s edict did move tattooing underground for Japanese people. And from that moment onwards in Japan, a tattoo signaled that you were a criminal.

From crime to medicine

Things continued like this until the end of World War II when the American military occupied Japan, which signaled a sea change in Japan.

Tattooing was legalized, and weirdly prostitution was criminalized. (It’s interesting what Emperor Meiji found objectionable and what he didn't, eh?)

The world of tattooing suddenly opened up again. And shortly after tattoos became legal, irezumi master Horiyoshi III had his first encounter with a tattooed yakuza. Something which might never have happened if tattoos had remained illegal. Read more about it in our piece on Horyoshi III.

While tattooing became legal overnight, attitudes weren’t as quick to change. Tattoos had centuries-long associations with the yakuza and criminality, so the popular perception was that tattoos = criminal. And this was reflected in the Japanese government’s decision in 2001 to classify tattooing as a medical procedure. Pushing tattooing back underground again.

The issue was taken a step further by the then-mayor of Osaka in 2012. Who called for a ban on tattoos for all public employees, saying that “employees with tattoos who didn’t want to remove them should look for work in the private sector.”

Needless to say, Japan’s relationship with tattooing has been rocky.

Newly legal

Tattooing eventually lost its requirement for a medical license. But only in 2018 and largely thanks to tattoo artist Taiki Masuda.

Source: savetattoo.jp

Masuda was swept up in a police campaign to prosecute tattoo artists. Along with several other artists in the city of Osaka, he was prosecuted and fined. But unlike many of the other artists, instead of paying the fine, he decided to fight his prosecution.

And thankfully, he did.

His fight led him to the Osaka High Court, which overturned his conviction and laid a precedent for tattooing without a medical license. And while tattooing isn’t likely to completely shed its stigma overnight, it’s moving in the right direction. Which, for us lovers of this great art form, is a welcome sign.

Want to dive into the world of Japanese tattoos?

Check out our books by master artist Horyoshi III Scrolls Junior or Book of Dragons by Bill Canales’. Or even go back to the place modern irezumi began by revisiting the Suikoden with Of Brigands and Bravery.

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.