The Flowers of Edo… that’s how the resident of Edo (now Tokyo) used to describe the fires which ravaged the city. And when you live in a densely populated city constructed almost entirely from wood, you have to have some kind of a sense of humor about something so devastating.

Source: National Museum Liverpool – Edo Firemen covered in tattoos fighting a fire.

During the 267 years of the Edo period, there were approximately 1,800 fires, with 49 being Great Fires. When you break that down, it means there was a Great Fire every five years. The largest was the Great fire of Meireki which killed over 107,000 people. So fires in the city of Edo had the potential to have devastating consequences.

There were a couple of reasons for this. The dominant building material at the time was wood and bamboo, the city was densely populated and expanding every year, and Edo’s local climate also being a factor. There was even a fire season (January until April.) During which time women would typically leave the city for their own safety.

Fire prevention

At the beginning of the Edo period, there was no civic firefighters. Rich merchants could afford to hire their own firefighters, called daimyō hikeshi. But their only role was to protect the property of their masters. The Shogunate also established a firefighting force early in the Edo period, but their sole responsibility was to safeguard buildings deemed valuable to the government. Up until the Great fire of Meireki, the general citizens had to fend for themselves, but after the devastation of this fire, the Shogunate instituted a civic firefighting system.

When a fire was detected, firefighters would assemble and use long hooks to tear down the houses beside them so the fire would burn itself out. Being a fireman was typically a part-time job, with most chōnin firefighters working as steeplejack or artisans.

Unlike modern firefighters, these firemen didn’t try to extinguish the fire. Their role was to stop it’s spread. They would do this by demolishing the houses on either side of the fire, to stop the fire’s spread. This method of fire containment as well as the trades these firefighters were drawn from contributed to their hard-nosed, aggressive reputation.

Edo firefighters

Source: rioleo.org – Machibikeshi firemen

Firefighters came in two categories: buke hikeshi from the samurai class and machibikeshi from the chōnin class. Even after the shogunate introduced civic firefighters, the daimyōs still maintained their firefighting forces. Private firefighting remained common, which lead to fighting between rival firehouses and competition to be the first fire force to a fire.

Firefighters of the Edo period had a complicated reputation. On one hand, they were local heroes, saving lives and protecting the city. But they also had a reputation of being coarse, raucous, and oversexed. There’s a famous story, immortalized in a Kabuki play, of a brawl between a group of firefighters and sumo wrestlers. The fighting was so fierce that the two groups battled it out for a whole day.

Source: The Public Domain Review

Stories like this and fights between rival groups of firefighters were commonplace and have been immortalized in woodcuts from that period. This led to Edo firefighters creating a reputation that was an equal part hero and delinquent.

The tattooed class

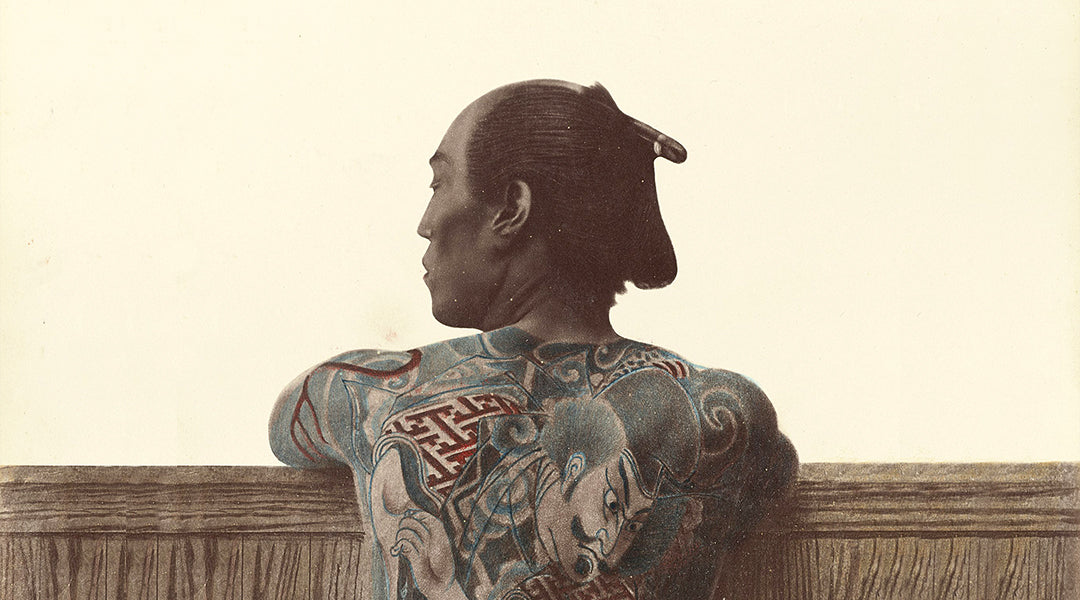

Like all groups who take part in dangerous jobs, firefighters found ways to show their allegiance to the group. And were often heavily tattooed.

Tattoos carried less stigma during the Edo period than later eras. Despite being banned by the Shogunate they were commonly worn and were a way to display antigovernment sentiment or signal your membership of the ‘floating class.’

Source: Wikimedia Commons – An example of the inside of an Edo fireman’s coat

Source: Wikimedia Commons – An example of the inside of an Edo fireman’s coat

Firefighters wore thick cotton coats (hikeshi banten) which they doused in water to protect themselves from fire. These coats were plain on the outside but were beautifully patterned on the inside with the pattern often matching the fireman’s own tattoos.

The coats were worn with the plain side out when fighting fires, but while celebrating, such as after successful extinguishing of a fire, or public event the patterned side would be worn outwards.

Tattoos were a way to display toughness and masculinity and provided spiritual protection. But the patterned coats and tattoos also made it easier to identify the body of firefighters who die in a fire.

Representation

Edo-era firefighters featured a lot in the woodcuts of the day due to their association as local heroes.

Source: stampcommunity.org – Edo firefighters with their tattoos removed

These Edo-era firemen have achieved an almost mythic status even in modern Japan, with the Japanese post office choosing to memorialize them in stamp form in 1998. However, the firefighters’ love of tattoos presented a problem for the stamp due to tattooing’s more modern association with organized crime. In the end, the post office decided to remove the firefighters' tattoos so as not to offend modern sensibilities.

Japan has slowly but surely come to see the beauty in their own tattoo art form, so maybe one day we’ll see the Edo firefighter represented as they were. But for now, the tattoos of these delinquent heroes will just have to remain under their cotton coats until their time to celebrate comes.

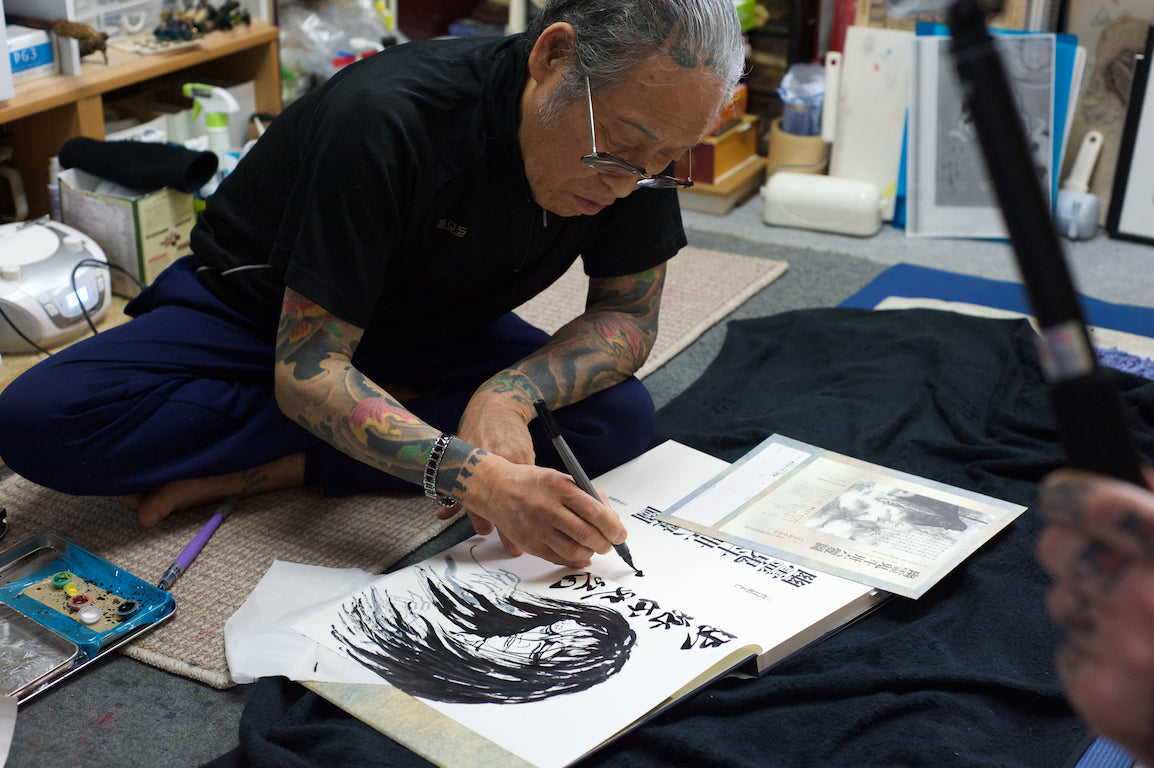

Artwork by Yushi "Horikichi" Takei

Leave a comment

This site is protected by hCaptcha and the hCaptcha Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.